Chapter 2

16 minutes

Lead scoring basics

There's a lot to think about in lead scoring. What data points should you use? How do you not get yelled at by sales? Is it okay to call it "lead boring" every now and then?!

In this chapter, we'll review elements commonly used in B2B lead scoring models:

- Using fit and intent data

- 2D lead qualification and keeping fit and intent scores separate

- ABM and qualification at the account level

- Product-led qualification: PQLs and PQAs

- Multiple lead scores for complex businesses

But first, let's talk about the point of scoring. You have two levers to pull as you scale your company: volume and conversion. We're focusing on conversion. Scoring is all about optimizing your conversion rates by sending the right types of leads to the right people to work them — the people who have the best chance to convert that lead at an efficient cost.

Fit and intent scores

A fit score indicates whether a company is a good fit to be your customer—and worthy of sales attention. It's calculated with fit data: details that make up a company's firmographic profile, such as industry, country, and number of employees.

A fit score can also include conditions about an individual person's role or department. For example, if you're selling a design tool, you might give a higher fit score to a lead whose title is "VP of Design" than to a lead called "Lowly Design Intern" because of the difference in decision-making power. And a "VP of Customer Success," as excitingly executive as they may sound, would score lower because they're not on a team that your tool usually sells to. Let's call this individual information “demographic” or “employment” data.

An intent score indicates a lead's likelihood to buy. While fit is all about whether you're interested in them, intent is all about whether they're interested in you.

Intent scores are based on intent data, collected from behaviors that indicate interest and engagement. An example of a high-intent behavior is a hand raise (submitting a request to talk to sales). Other examples include signing up for and using your freemium product, reading your eBooks, or visiting your website.

Website activity is a great source of intent data, because it can signal a number of things about readiness to buy, including:

- The type of information a lead is interested in (e.g., visits to certain product pages or blog posts can give sales a hint about what to talk about on a call)

- How many people at the entire account are interested (e.g., just one person poking around, versus five people from the same company visiting at the same time)

- Visit frequency (e.g., if the number of web visits from a high-fit account surge 10x in just two days, you might want to send a Slack alert to the sales team so they can reach out)

- Purchase readiness via high-intent pages (e.g., visits to the pricing page or implementation docs)

You can get firmographic and individual data about your visitors with Clearbit Reveal — even for anonymous website visitors. Reveal uses a reverse IP lookup and other signals to determine which company the visitor comes from.

Fit and intent scores can apply to individual leads, as well as to accounts (the entire company they work for). In a moment, we'll talk about why it's important to think about account-level scoring, especially as you move upmarket.

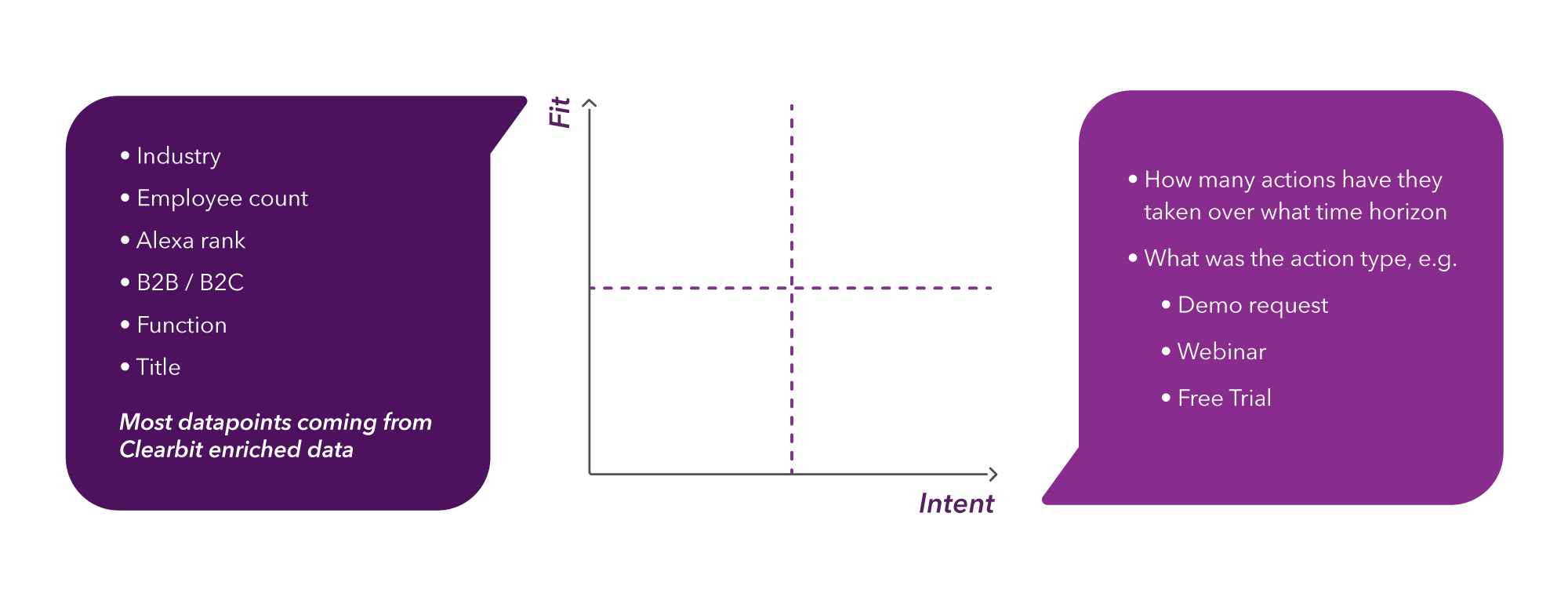

Two-dimensional (2D) lead scoring

When you put fit and intent together, you get 2D scoring. The term simply means that you're taking into account both fit and intent when you decide which leads to send to sales, to nurture, and so on—instead of just one aspect.

You'll need to calibrate how much weight to give fit and intent for your company's unique situation, and where to designate the fit and intent "thresholds" for qualification (e.g., when you'll send a lead to your sales team). Your standards will depend on factors such as the size of your sales team, how many leads they can handle, and their level of training for different types of leads. You can move those thresholds as your sales team's capacity changes and your company's strategy evolves.

For example, at Clearbit, when our sales team expanded capacity, they all of a sudden were able to effectively reach out to marketing-sourced leads—folks that haven't raised their hand yet, but are engaging with our content, ads, and website. So we started looking at a lead's engagement behaviors and intent data to decide when they're "warm" enough to send to sales (and what fit score will disqualify them). This is an ongoing process where we're figuring out and adjusting how much to "open the tap," loosening and tightening it based on sales feedback, their team capacity, and our current company strategy.

Fit scores are the gatekeeper for sales attention

Every company has different needs, so we're not going to tell you exactly how to configure a two-dimensional model based on fit and intent. But we do have a rule of thumb that will work for most companies once they start growing their sales teams: make fit scores (not intent scores) the main gatekeeper for sales attention.

It can be tempting to keep talking to high-intent companies with just an "okay" fit because they're low-hanging fruit. But they can distract sales from working excellent-fit companies. Let your AEs, senior sales talent, or dedicated teams (ABM, BDRs, etc.) focus on high-fit prospects, even if they have low intent, because good salespeople can create and develop purchase intent where there was none. You can't change a fit score, but you can influence purchase intent via sales and marketing.

Taking this rule of thumb a little further— again, if you have the sales resources to do so—consider giving more weight to account fit than individual intent and fit.

The "Lowly Design Intern" from a perfect-fit company may be a good lead to send to sales. Even though they have no purchasing power, an AE can use them as the entry point to develop a relationship with the entire account. This lead is more valuable than a decision maker like the VP of Design from a poor-fit company, even if they show a lot of purchase intent.

Legendary CRO Mark Roberge puts it well on the State of Demand Gen podcast:

"If the intern at a great-fit company subscribes to your blog, a good salesperson will navigate up from the intern to the decision maker. A demo request from a non-fit company will distract the AE from working with the intern at a perfect company."

Even when company fit is the first line of qualification for sending a lead to sales, intent still plays an important role. For example, it can help you prioritize within high-fit accounts, if you have more of them than you can manage, or help you get the timing and personalization right when a high-fit account shows a lot of recent activity. It's another lever to play with as you open and close the tap.

Keeping fit and intent scores separate

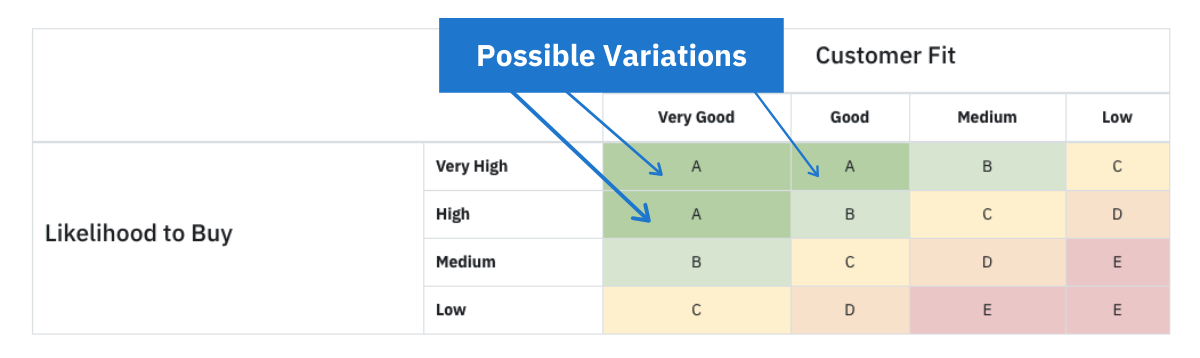

When we talk about combining fit and intent scores, we don't mean you need to literally combine them into just one blanket score (e.g. "this lead scores an 87"). It can be helpful to keep fit and intent scores separate.

Why? For one, combining fit and intent in a way that obscures priority or potential deal size sends lower-fit, lower-value leads to sales.

source: Madkudu

source: MadkuduTo illustrate the confusing blending issue this produces, in this chart a combined letter grade of "A" can mean that a lead has:

- a very high likelihood to buy and very good customer fit, or

- a high likelihood to buy and very good customer fit, or

- a very high likelihood to buy and good customer fit.

That could be more clear, right?

Jess Cody, Product Marketing Manager at MadKudu, explains: "A lead with a letter grade of 'A' may be extremely active on your site, booking a meeting, reading blog content, and more, but they may not be the best fit for your company — for example, their company size and technologies used might not be ideal."

Leads with different fit scores should be getting different journeys (e.g., routing to different sales teams or sending enterprise leads to sales and high-intent SMB leads to self-serve tracks). Keeping scores separate supports that, and ensures you don't distract sales reps, no matter how many flames a lead has. 🔥 🔥 🔥

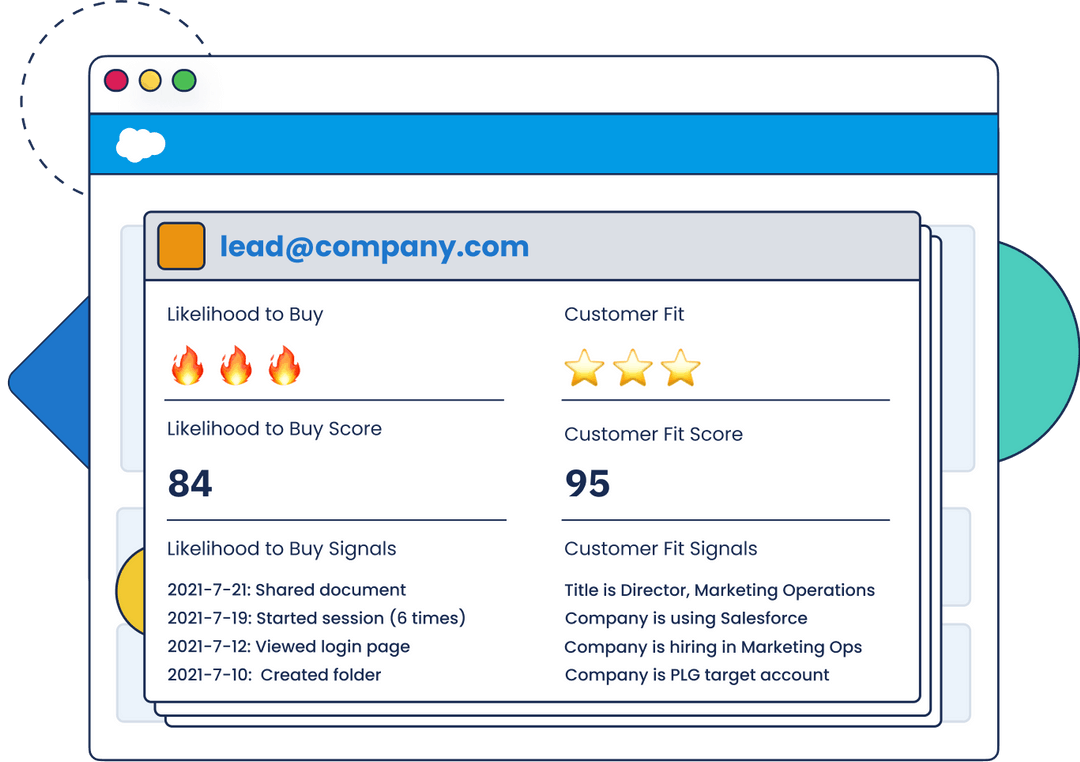

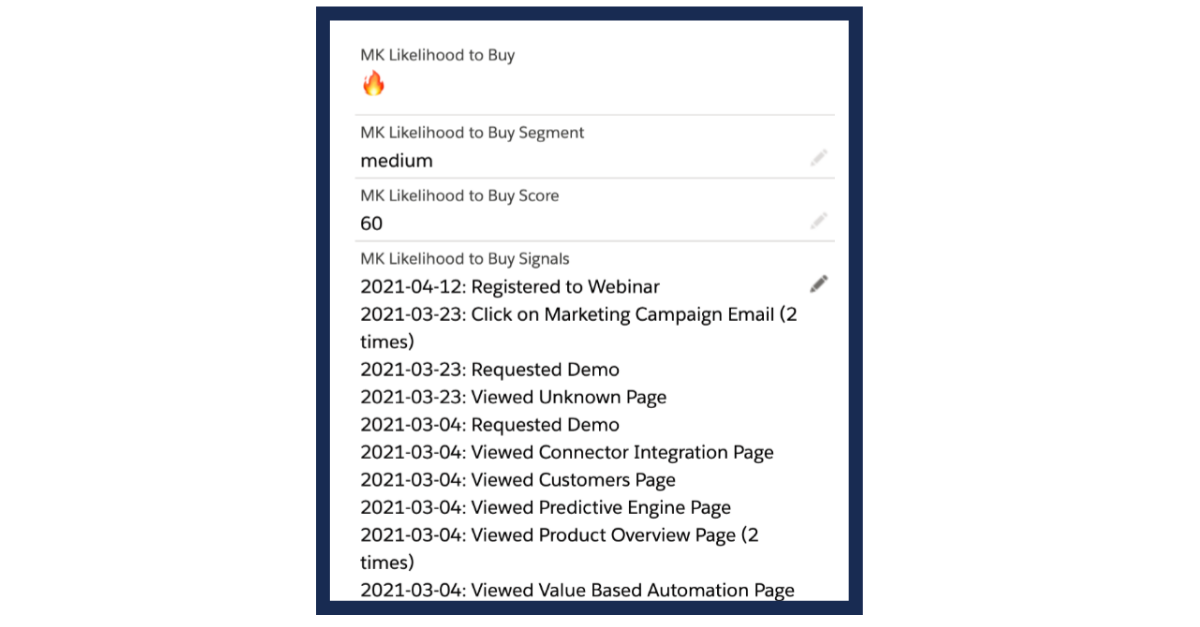

To illustrate, MadKudu scoring has one score for Customer Fit and one score for Likelihood to Buy. They're shown below, along with itemized Customer Fit Signals (e.g., Director title, Company uses Salesforce) and Likelihood to Buy Signals (e.g. Started session 6 times on 7/19/2021).

The letter and number score

Another approach we've seen at Clearbit is to use two fields, where fit gets a letter grade and intent gets a number score. The fit letter stays stable over time, while the intent score moves up and down.

To illustrate:

- A grade for high fit, and a 2 score for low intent = A2

- D grade for bad fit, but a 10 score for high intent = D10

Instead of talking to the D10, sales should spend their time nurturing the A2 into an A10.

How marketing can use fit and intent scores to direct acquisition and nurture efforts

When marketing is designing campaigns, they can prioritize fit over intent, and vice versa, depending on whether they're doing acquisition or nurture marketing.

Pre-acquisition: Acquisition marketing should focus on using the fit score to acquire as many high-fit leads as possible. Jess says, "For acquisition programs, it's key to focus on driving very good-fit leads. At the top of the funnel, successful marketers optimize their campaigns to find the right profile of people for their business."

Post-acquisition: Nurture marketing should focus on intent score. Once leads come in, you can't change their fit. This is your chance to influence their likelihood to buy. "You've got the leads; now you have to figure out what to do with them," Jess says. "Build nurture campaigns and programs to progress people through the funnel. Understanding a lead's likelihood to buy and what actions they have taken will help you craft more informed programs that drive conversions, and, ultimately, opportunities."

"Itemizing" behavioral scores for sales

Jess also recommends breaking down intent scores so that sales can see a lead's actual behaviors. It's helpful for reps to know which webinar the lead registered for, and which product pages they visited on the site, for example. Jess says, "Sales teams don't always care about the number or letter of the score (or the number of flames), but having visibility into why someone is scored a certain way and what they have done is essential in crafting personalized outreach."

She adds, "Providing behavioral context empowers reps to reach out with the right message. Looking at the signals below, a sales rep could follow up with content related to the webinar, ask if they have any questions about the pages they've viewed, or share relatable stories of customers with similar challenges."

This transparency not only makes better sales conversations, but helps build trust and align sales and marketing around a scoring model.

ABM and qualification at the account level

If you're moving upmarket and selling to larger companies, it's critical to score at the account level and consider the dynamics between individuals within the company.

Make sure you know your hand-raisers. The larger a company is, the bigger the gap between the people who use a product and those who buy it (the hand-raisers). In a sense, buyers are the "true" leads, while users are activators and enthusiasts who influence the buyers internally.

If you make a service or product for developers, a developer might qualify as a perfect lead when you're selling to individuals and SMBs. But once you sell to enterprises, a perfect lead might actually be someone on the IT team, a procurement manager, or the VP of Engineering.

It all plays into the idea of account readiness. Just because one developer is your superfan doesn't mean the entire company is ready to take on your solution for their broader organizational challenges.

Moving upmarket may require a top-down sales approach to infiltrate an organization, figure out their problems, and develop relationships with the buyers. Some companies use this top-down approach for account-based marketing (ABM), where they identify perfect-fit accounts and compile them into target lists. This takes the fit-intent spectrum all the way to one end, where sales places utmost importance on fit, and then tracks and nurtures intent for accounts within their fit boundaries.

Product-led qualification

A product-qualified lead (PQL) is a lead that's been qualified based on their activity in your product, and whether they've experienced meaningful value from it.

This is typically used in the context of a person using your product's free plan or free trial, because if they've already seen your product's value and use it regularly, it may be easier to upsell them to a paid plan. Same goes if they're on a lower-cost individual or self-serve plan and good prospects for a larger enterprise plan for their team at work.

When you scan your user base for people who have high in-product activity, you can identify which user-leads to upsell, and how. For example:

- Tasking sales or triggering emails to reach out to certain users proactively

- Sending nurture emails about premium features

- Showing an in-product message inviting them to contact sales or swipe a credit card to upgrade (self serve)

For more details on what a PQL is and how to start using PQL metrics for every team at your company, see Wes Bush's guide to PQLs over at ProductLed.

A product-qualified account (PQA) is qualified at the company level instead of the individual level. When you think about PQAs instead of PQLs, you're considering how buyers and users may be different people, how they influence one another, and how you need to approach them differently with your marketing and sales efforts.

A PQA is a product qualified account, but the real leads you're after are the buyers at that company. These buyers are not necessarily going to show up in your user base.

So you can have a PQA, or what looks like a hand-raiser, without having a true lead at that company yet. You might need to do a lead and outbound strategy to find the buyer at that account.

This consideration gets more important when you're selling a product to large companies, where it's less likely that product users and buyers are the same people. Elena Verna (growth advisor at Reforge, MongoDB and more) analyzed the hand-raisers at product-led SaaS companies and found a pattern: on average, fewer than 40% of hand raisers from PQAs were also true users. And if they were, they usually came from smaller companies. Another 30% of hand-raisers didn't have a user ID in the product at all. And the remaining 30% were “evaluators”: they were recent sign ups within a more mature account. They'd only created an account to poke around, assess, and buy it for their colleagues who'd been using it.

You can do the same analysis if you're product-led and have a hand raise motion. Pull a list of your past hand-raisers and look at their email addresses. How many of them are registered in your user base? For those who are registered, figure out how old their accounts are, and check how much in-product activity they have. If their accounts are young and don't show much activation, they may not be a real user, but rather a buyer at an account that's being influenced by their colleagues.

If your users and your hand-raisers don't overlap much, you need different motions to reach and influence them, and different journeys to send them on.

Multiple lead scores for complex businesses

Most companies need just one lead score, ideally keeping fit and intent separate within that one score. But for complex and high-volume businesses, it can be helpful to have multiple lead score formulas that operate separately to serve distinct business areas, such as:

- Different products

- Different customer segments, such as geography, industry, and size

- Different GTM motions, such as a self-serve/velocity motion, an inbound sales motion for hand-raisers, and a white glove enterprise motion.

It's all about matching a lead scoring model to specific situations, needs, and goals.

For instance, if you're using machine learning to score — also called predictive scoring — you're using past data to guess whether a future lead is a good one. But when you expand to a new market, the data that worked before may not apply to your new focus. Colin White, our Head of Demand Generation at Clearbit, explains: "When you're using machine-learning scoring and want to go after a new market, you can't rely on your original score anymore. The data behind that first score doesn't take into account information about the new market you're trying to tackle."

Same goes for different motions — like a product that has a self-serve velocity track as well as a sales motion for midmarket and enterprise leads.

Predictive scoring models are optimized for specific outcomes. For example, a model that is scoring leads for a sales team may be optimized for opportunities with a deal close probability of 60% or higher and a deal size amount of $100,000 or higher.

An individual from a large public company with a large budget would have a very high-fit score. An individual at a small company with a small budget will have a low-fit score, and wouldn't be sent to sales. However, that low fit score lead may actually be ready to use the product and swipe their credit card, making them a great fit for your company's PLG motion.

In this situation, a separate model (and score) is necessary to evaluate the fit and likelihood to buy within a velocity motion.

So as you can see, as a company grows and becomes more complex, lead qualification becomes more complex, too. In the next chapter, we'll share guidelines for finding a scoring setup that matches your business maturity and doesn't hold you back.