Chapter 1

15 minutes

The Key to Saas Pricing

Kyle Poyar Director of Market Strategy at OpenView

In September 2009, Andy Wilson learned that Inc. Magazine had named his company, Logik, #181 on their list of the fastest growing businesses in the US. He had grown the e-discovery services company 1,067% over the prior three years to $4.4 million in revenue. It was profitable, too. Logik had just eight employees and brought in a $3 million profit in 2008.

That same year, the recession hit and Andy made an unconventional decision. He decided to shut down Logik’s core business and transform the company from a services business model to Software-as-a-Service (SaaS). Even though his business had been highly successful, Andy realized it was ripe for disruption. “We saw the future and it was not humans managing hard drives and creating databases. That’s going to be done by software. Software can do a better job, and it’s going to do a better job,” he says.

Andy and his cofounder, Sheng Yang, set out to rebuild Logik from the bottom up, leveraging automation and software to streamline the process of managing digital information so companies could do it themselves without needing an expensive third-party vendor. Andy counted 2,500 steps that were required to fulfill a client request as a services business. His goal was to cut that down to three steps or less with their SaaS offering. This would make it fast and easy for corporate legal teams, law firms, and investigators to organize, search through, and review a lot of unstructured data, a process they refer to as e-discovery.

After several years of development, Andy was ready to release the SaaS offering to the market, now branded as Logikcull. There was only one hitch: pricing.

He knew he didn’t want to price like the services businesses of yesteryear, but beyond that he had no idea how to structure his pricing. The e-discovery market had been dominated by old-school, legacy services companies that charged exorbitant fees. “There’s a data fee for everything. It’s really unpredictable and can explode on you in a number of ways, like if you had 100 GB of data you needed to sift through, if you went with a legacy e-discovery provider that would probably cost well over $100,000 just to get it indexed and posted for review. And it’s probably going to take a week or more of time,” he tells me.

Compared to this old-school process, Andy’s new technology saved time, kept data more secure, and opened up new use cases beyond e-discovery. Customers would be able to speed up the e-discovery process so it takes minutes or hours rather than weeks, cutting manual labor and associated costs. In other words, the product did a lot more than legacy systems, and he wanted to capture the additional value.

Andy’s first step was to list the problems that he wanted his new pricing model to solve for his business. Two were top of mind: lumpy revenue and the commoditization of data. “One of the biggest [problems] was the lumpy revenue problem that you see in episodic types of business models … You’re really in a weird state of unpredictable business growth. So, we wanted to solve that by creating a subscription [model]. We also wanted to move away from commodity types of pricing models and the biggest commodity being quantity of data.”

Andy had one other rule of thumb. He thought that in order to get lawyers to be willing to change their habits, the company would need to provide orders of magnitude more value than existing solutions.

To overcome the inertia of the market and lawyers’ reluctance to buy new products, in other words, Andy couldn’t just rest on having a far superior product. He also thought he needed to launch with a cut-rate initial price point.

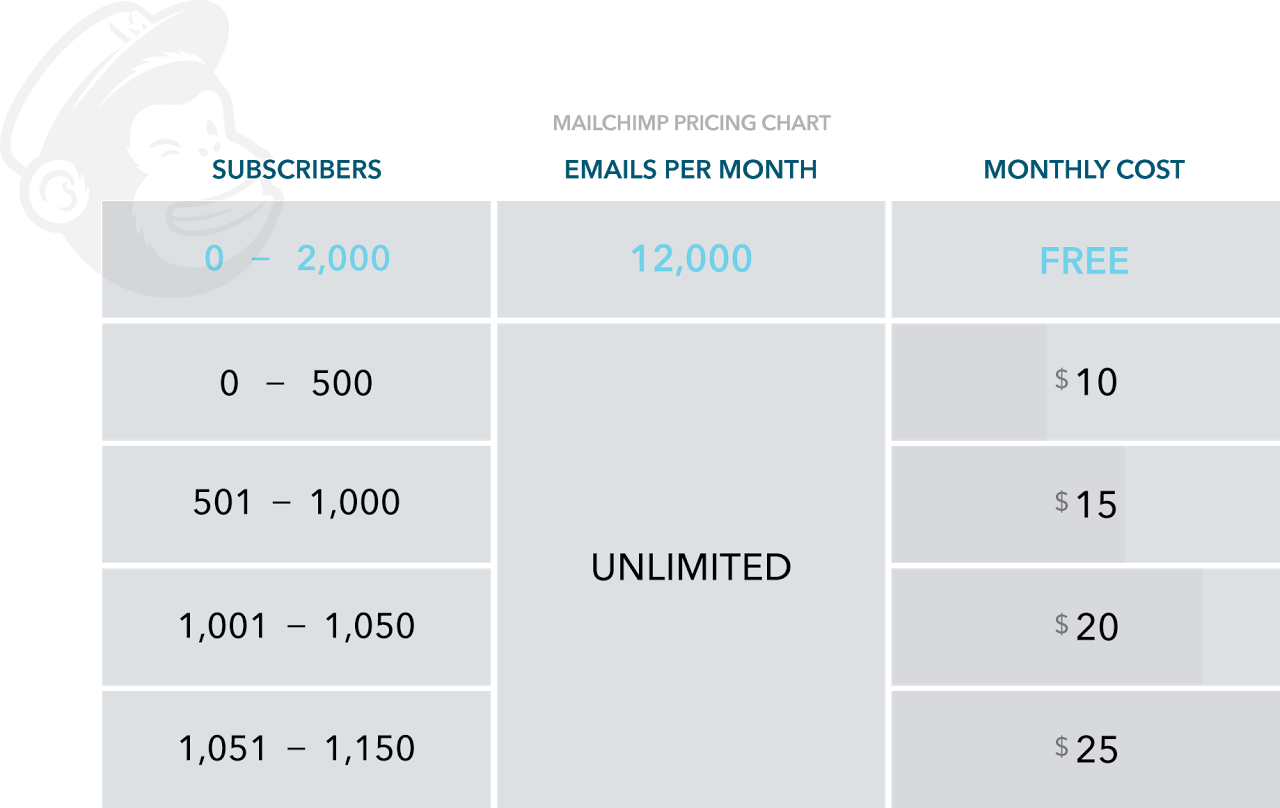

He decided to start simple: he launched a straightforward subscription model similar to that of MailChimp. The Atlanta-based email marketing provider ties its subscription pricing to the number of marketing contacts a customer uploads and sends emails to, rather than the amount of storage taken up by those contacts. Andy decided to try a similar model and charge customers based on the number of documents they wanted to host inside Logikcull. He set an extremely low price of $0.13 per document per month, which worked out to a much more affordable rate compared to the hefty gigabyte (GB) storage fees customers were paying legacy providers. He liked that this pricing model created a steady subscription revenue stream and shifted away from the amorphous gigabytes of data stored toward a metric that he thought would be easier for lawyers to wrap their heads around.

Unfortunately, customers hated it. Unlike MailChimp customers, Andy’s customers had no idea how many documents they were going to have, so document-based pricing wasn’t any easier for customers to predict than gigabytes of storage. Even worse, Andy couldn’t tell a customer how many documents they would need “because the job of Logikcull is to unpack all this information,” counting up and de-duplicating all of the files that a customer puts into the system. Only after a customer used Andy’s product would they truly know their document count and hence the price they would have to pay. Customers’ document counts fluctuated over time, too, which made it difficult for them to commit to a given subscription tier. Andy knew this would ultimately hurt his business, since many finance teams won’t sign off on a deal unless they know the exact price they’ll have to pay at the end of the year.

The solution: Start listening to your customers

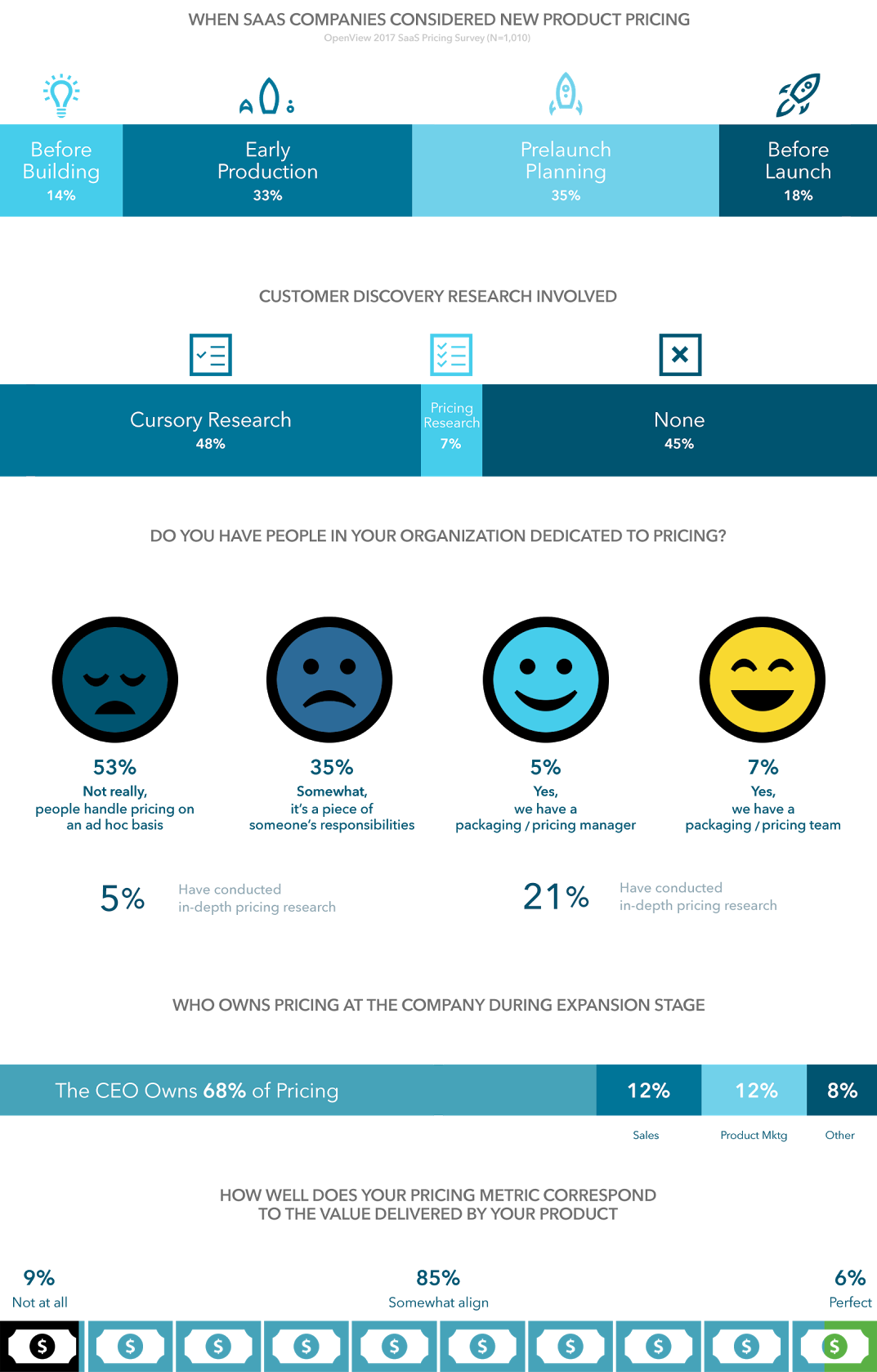

In a survey of 1,000 SaaS companies conducted by OpenView, we learned that—like Andy—50% of companies procrastinate on pricing decisions. The survey showed that the majority of companies consider pricing either right before or as their product is getting ready for launch, rather than toward the beginning of the development process. Often, pricing decisions are made with little or no data. At most early-stage companies, pricing isn’t a part of anyone’s job description and gets left to a CEO who’s already constrained for time.

x.ai, the AI personal assistant, took a different approach when they went to market with their initial paid offerings to great fanfare in October 2016. They carefully conducted in-depth research on pricing from beta customers, using surveys as well as in-person roundtables to gather input. Similarly, it’s how Meetup built demand for and monetized their successful enterprise product after trying and failing several times to crack the code on how to sell to the B2B market. Meetup asked businesses what new features they would find most valuable and how much of a premium they would pay for these enhancements.

After Andy’s initial pricing misfortune, he vowed to take a more data- driven approach to pricing that put the customer front and center. He went out and talked to dozens of Logikcull’s customers and prospects and learned that customers wanted predictability more than anything else. The challenge was making that work for his business. “You need to come up with a model that satisfies that and also aligns with value in the best way possible, which is not necessarily easily predicted at the beginning.” But rather than dwelling on generating a predictable revenue stream for his own business, Andy chose to create predictability for his customers.

This insight led Andy to shift their pricing model from per-document pricing, which had caused friction, toward pricing based on a combination of users and data. For example, a law firm could subscribe to a package that offered full access to Logikcull for five attorneys at a time, along with a generous 100 GB of data storage. If they ever needed more data later on, they could easily top up their subscription with a low per-GB fee for the overage, since data would not be the sole driver of the pricing. This new approach made it much easier for customers to budget for Logikcull and reinforced the value of the software independent of commodity cost of storage. It also appealed to Logikcull’s wide array of customers, including law firms, corporations, and governments.

Andy’s new pricing model is an example of what economists refer to as a three-part tariff. Rather than charging a customer for each incremental unit of usage, in a three-part tariff there is a base platform fee that includes an initial amount of usage. That means a customer can predict with near certainty how much they will be billed for. But a sliding scale is built in so that if they use more than their allocated amount of data, a business like Andy’s isn’t stuck with the bill. In other words, the customer gets 90% predictability, but the service provider (Andy) can model the pricing to ensure the maximum value is captured from each customer.

Linear Pricing (LP) - Each hosted document costs $0.10. 2 Part Tariff (2PT) - The software has a base platform fee of $10,000 and each hosted document costs $0.10 more. 3 Part Tariff (3PT) - Again, the software has a base platform fee but the fee is $25,000 because it includes the first 150K hosted documents are free. Each additional hosted document costs $0.15.

See Three Part Tariffs by Tom Tunguz for a full explanation

Research indicates that this type of pricing leads to higher customer satisfaction because customers don’t experience the same pain that they do when they have to pay for each amount of incremental usage. For finance teams, this is especially valuable because they can accurately model all of their costs into projections. That in turn removes psychological and financial barriers and leads to faster sales cycles for companies like Logickull.

In talking to customers about his new pricing model, Andy started to pick up on other valuable insights as well, such as new use cases for the product. He trained everybody in the company to ask simple, open-ended questions like “What are you using Logikcull for?” Then, to make sure it wasn’t a one-off use case, he would talk to potential customers in the same segment and see if they had the same problem.

As Andy built a longer and longer list of use cases beyond traditional e-discovery, he started training the sales and account teams to accelerate product adoption within existing accounts by expanding the number of use cases. More use cases meant more users would want access to Logikcull and more data would be brought into the software, giving Andy two separate levers to upsell customers. In one example, Andy sold a corporate legal team on the traditional e-discovery use case and expanded to six departments afterward. “We just said ‘Hey, could you introduce us to the tax team? We talked with customer X and they have this problem, and apparently Logikcull is really good for that issue.’ Before you know it, it starts working its way up.”

Once they get a customer in the door, Andy now knows that Logikcull has a great shot at growing that customer’s spend by 2x, 3x, or even up to 20x within a single year. Seeing that rapid expansion opportunity led Andy to formalize their process for identifying top candidates for an upsell. He recently instituted an account-based metric in Salesforce indicating the total available subscription they believe is possible. Now he pushes his team to achieve that goal over time rather than all at once. “I probably say this every day with the sales team,” Andy said. “Just get them in the door. Stop trying to maximize the initial sale because that’s just the first bite. You’re going to get multiple bites.”

Customer discovery further helped Andy hone the way he measured and communicated ROI to customers by accelerating their already impressive land-and-expand business model. Logikcull’s main ROI is efficiency, so Andy’s team keeps track of a customer’s time spent before and after adopting the product. “We do before-and-after studies whenever we’re kicking off a new customer. We’ll ask things like ‘How long does it take you today, on average?’ and ‘How many times do you do that?’ and we’ll record that. Then we’ll ask, ‘Now, in Logikcull, how long does it take you?’ All of a sudden, we have a much more compelling story. We can arm our internal champion with really clear ROI data so that when they walk up to the person that has budget, it’s a no-brainer.” Depending on the use case, Andy captures different data points so that the ROI story is as compelling and personal as possible.

How to implement customer development into your own pricing

When Andy advises early stage companies on pricing today, he suggests that they rapidly get started with their own customer development for pricing purposes. He says, “It starts with talking to customers and asking simple questions.”

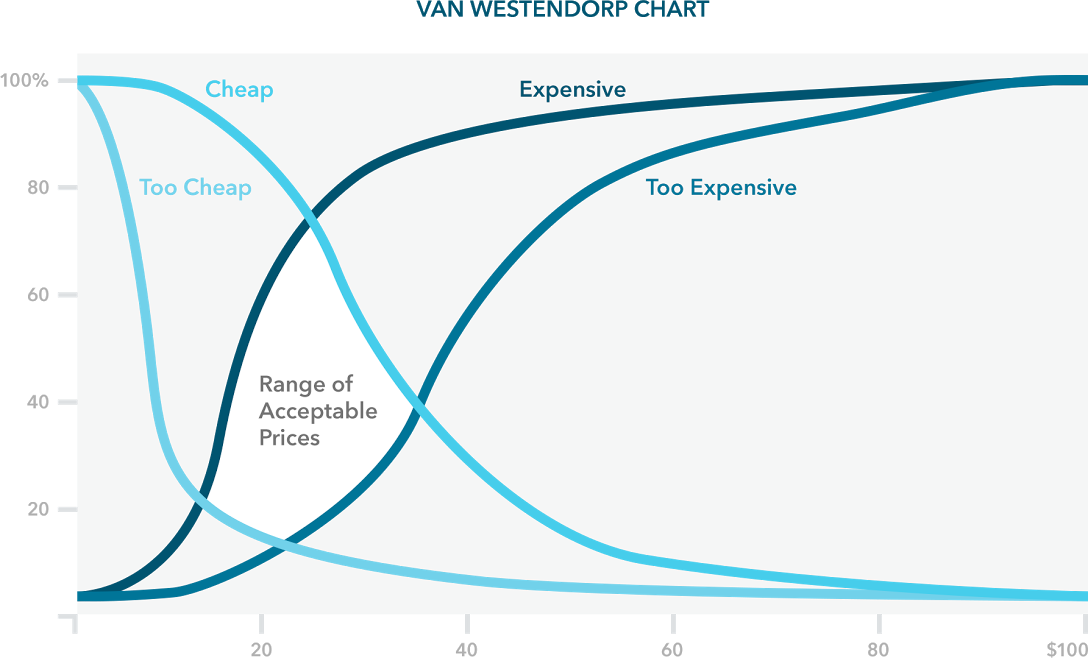

What Andy’s describing is the Van Westendorp Price Sensitivity Meter, a pricing technique named after its creator, economist Peter van Westendorp, who was the first to suggest that directly asking people how much they would pay for a product would result in junk data. His method solves that problem by measuring buyers’ preconceived notions of different price points. He asks at what price point a product would be (1) too cheap to have faith in, (2) a bargain worth paying for, (3) expensive enough to seem reliable, or (4) too expensive to purchase. The goal is to put the respondent in a different state of mind when they answer the questions, away from how much they have to spend and toward how they perceive the price and value of the product. By asking a series of questions, van Westendorp collects a richer set of data that reveals the price sensitivity of a buyer across a range of prices instead of just one data point.

The results of each of the four price points are then plotted together on a graph, and the intersection of the lines reveals a target price range for the product. Pricing toward the lower end of the range would enable a penetration strategy, whereby a company pursues the most adoption possible while keeping a credible price point so buyers don’t doubt the product quality. Pricing toward the higher end of the range, meanwhile, enables a skimming or profit-maximization strategy.

The Van Westendorp graphs reveal key psychological thresholds in the minds of buyers, too. For instance, if a large contingent says that at $50 per month the product is getting expensive, the company would likely find a large drop-off in demand from pricing at, say, $55 versus $49. That drop-off in demand would be far larger than pricing changes further away from psychological thresholds; for instance, a price of $49 versus $43.

Unlike more complex pricing sensitivity tests, the Van Westendorp technique can be done with a relatively small sample size; the data can come from one-on-one conversations or an inexpensive online survey of buyers. But one risk of the Van Westendorp technique is that savvy buyers may lowball the price points they offer up so as to minimize the resulting price of the product. To offset that risk, economists recommend asking indirect pricing questions to get more context on buyers’ thought processes and switching costs.

Direct questions

- What do you think is too expensive of a price that you wouldn’t buy it?

- What’s too cheap that you wouldn’t trust it?

Indirect questions

- How do buyers think about the value and ROI of the solution?

- How would they pitch the business case to their boss?

- How does the buying process work, and what’s the threshold for a deal to go to procurement?

- What would be the risks of no longer using the solution?

Contextual questions helped Andy realize that regardless of how much value his product delivers, when selling into government, it’s best to avoid procurement at all costs. Through customer discovery, Andy found out that one government buyer had a budget threshold of $10,000 per year before a purchase had to go through a formal RFP process. This would include the dreaded security audit and lots of bureaucratic red tape. Not only would procurement slow down a deal, it could kill a deal entirely or bring a new competitor into the mix.

Andy decided that he would come up with a pricing model that accommodated this customer need, even though it was much lower than his typical deal sizes. Lo and behold, that customer “went from $10,000 a year to $200,000 a year for three years because we came in at a price point they could actually start with,” Andy said. Once he got through the initial purchase hurdle, Andy knew that subsequent product expansion would be subject to much less scrutiny and procurement meddling compared to the first sale.

Looking back, Andy regrets not adopting customer discovery sooner. “If you can have enough of these conversations, I think you’re going to get a much better view about the world. That would be incredibly helpful for any entrepreneur. My experience is similar, except I did it after the fact.”

Despite arriving late to customer discovery, Andy points out that it’s had a powerful impact on his business, especially when he adds up the dozens of pricing experiments he’s conducted over the years.

Andy’s SaaS business has far eclipsed his old services company, and now, armed with a new $10 million funding round, the future of Logikcull looks brighter than ever.