Chapter 8

12 minutes

Sales Operations

Don Otvos Head of Solutions Engineering at Salesloft

In the winter of 2010, I walked into Yammer’s headquarters in San Francisco to interview for a sales operations job. At the time, Yammer was one of the hottest companies in Silicon Valley. They had just moved to San Francisco after spinning off from Geni and were on the cusp of a hiring spree. The company was featured in tech press nearly every week after recently winning TechCrunch Disrupt, and its founder, David Sacks, had just raised millions of dollars from his fellow PayPal mafiosos. But when the VP of Sales walked me through the sales floor that first day, I thought I was walking through a college library during finals week. It was dead quiet. By that point, I had been in sales for a decade and I knew that nothing was worse for a sales team than a floor with no noise.

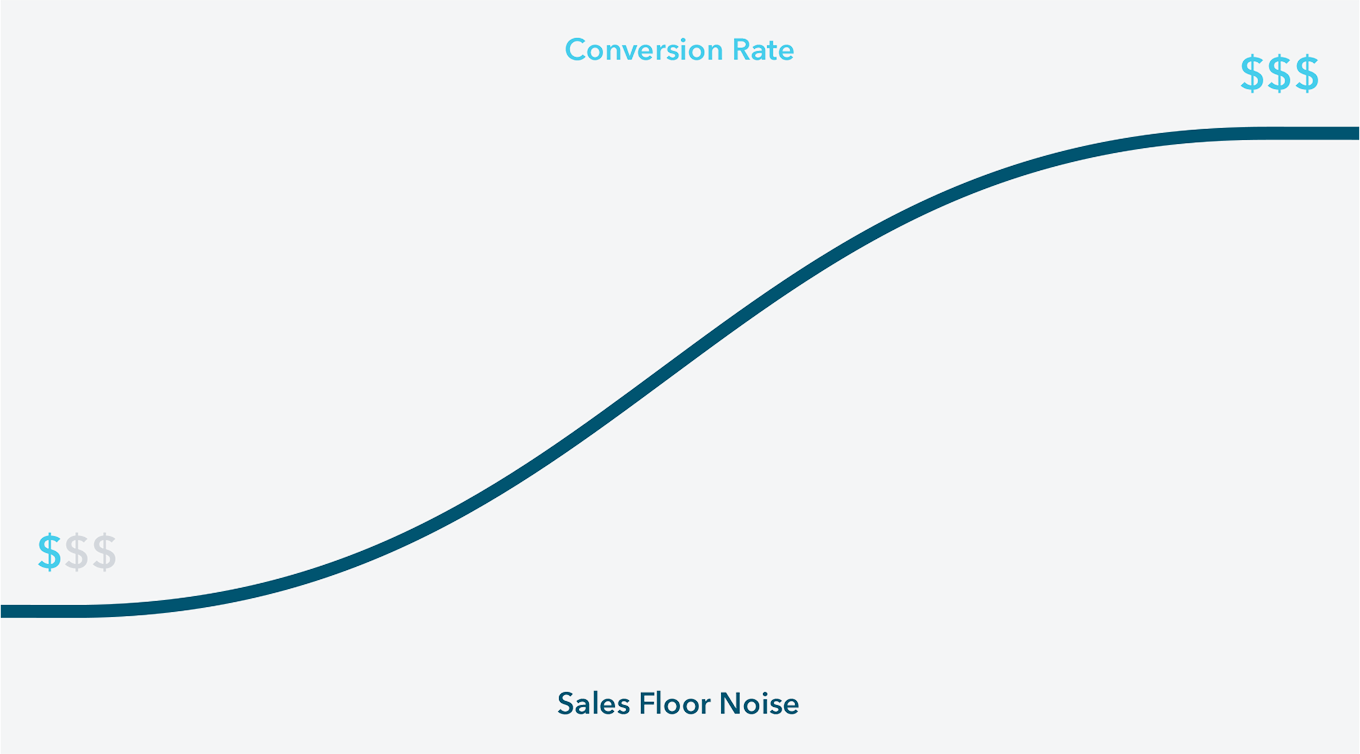

It’s been seven years since my early days at Yammer—a lifetime in Silicon Valley. Since then, the sales technology landscape has been flipped on its head more than once. Billions of dollars have been invested in making the modern salesperson’s job more efficient through various apps and workflows. Often, it is up to the sales operations team to implement those technologies. But for all the change the industry has seen, I believe that the role of sales operations is still the same: it is and always will be about enabling salespeople to spend as much of their day as possible selling and as little time as possible doing tedious work. In other words, our job is to keep the sales floor as noisy as possible.

Until robots replace the salesperson entirely (don’t hold your breath), noise level and revenue growth will have a near-perfect correlation. When a salesperson isn’t talking to a prospect, they are usually doing busy work like entering data in the CRM or researching companies—work that shouldn’t be done by a rep making north of six figures.

That first day in 2010, I told David Satterwhite, Yammer’s recently hired VP of Sales, “It’s so quiet in here, I think I heard a pin drop back there.”

“Why do you think we’re interviewing you?” he asked with a laugh.

A couple of weeks after my first interview, I joined the company. Not everyone was so welcoming of my critique in those early days, though. At lunch during the first week, I told one of the salespeople that it was strangely quiet. He jumped into a list of reasons: “We’re working smarter, not harder on this team … We use the latest technology, which means we don’t have to spend as much time on the phone.”

“Doesn’t the latest technology help you spend more time talking to prospects?” I asked rhetorically.

Needless to say, I wasn’t the most popular person at first. But it didn’t take long until they came to appreciate the value of sales operations.

When I joined Yammer, the company had acquired hundreds of thousands of “freemium” users. But the only information we collected at sign-up was an email address. We kept this low barrier to entry in order to increase sign-ups. Of course this was no help when a sales rep wanted to sell the paid version of our product. They had no context for which industry the company was in, or who they were emailing at the company, or even where that person was located. Therefore, reps were spending hours researching prospects before they reached out to sell them on the premium version of Yammer. That first summer, I set out to fix that.

One day I sent a message on our Yammer network asking coworkers if any of their kids were home for the summer and needed internships. Within a couple of weeks, I took over a conference room and six interns were spending eight hours a day researching companies and updating records in Salesforce. We were able to identify our most active users and most active networks to work on first, and then worked down the list.

Not only was I able to use this information to design our sales territories, but with more context sales reps were able to send a targeted email to the right buyer at a company based on our win/loss analyses. When a prospect in the manufacturing industry answered the phone, one of our reps could now share a relevant use case from a similar company in that first conversation. But more importantly, our added precision—and subsequent increase in conversion rate—cost less money since we had divided the labor into high- and low-skills tasks.

At the end of that summer, we expanded our office from an old traditional cube layout to a new honeycomb style with an open floor. I couldn’t help but smile when complaints started coming in that the noise on our floor was getting too loud. Sure enough, revenue was growing like a weed, and sales performance was at an all-time high.

Lesson 1: A quiet sales floor is your canary in the coal mine

Later that year, Peter Fishman, Yammer’s Head of Engineering at the time, came to me with an idea. He and his team had been building out reports and databases to track two of our most important metrics: engagement and virality by network. We knew anecdotally that we had the most success selling our product into accounts where the freemium version of Yammer was “going viral” and being adopted quickly. We also knew that if Yammer grew too fast in an organization, the IT team was more apt to shut it down. So it was essential that the sales team prioritize their outreach and target the IT team for a call. But simply giving reps a list of the most active networks wouldn’t work, since some of those companies were slow to adopt industries or small businesses. Peter’s idea was to marry the database that our army of interns had compiled with the backend database.

Together with Peter’s team, we created a data warehouse where we stored the firmographic account data from the CRM with the product usage data from our backend database. The idea was to leverage this information to run reports to learn where to focus our sales efforts.

One of the first reports we ran was the geographic location of our most active networks. The results were surprising. Adoption was strongest in the Netherlands, of all places. When we called one of our biggest customers in that country, they explained why it was so popular with the Dutch. An executive at the company, Wolters Kluwer, told us, “In the Netherlands, companies have a very flat organizational structure. It’s not uncommon for an average employee to share an idea with their CEO. Yammer enables this communication in a very elegant way.”

Of course, this was important to know because it informed where we invested sales and marketing dollars. We quickly began to focus efforts on freemium users in the Netherlands—a country that wasn’t on our radar months earlier—and other adoption hot spots.

Over the years, I’ve learned that the sales operations role is more quarterback than kicker. We’re not the janitors at a company tasked with cleaning up messy data; we’re the people whose work informs business strategy. Without accurate (or any) data, it’s difficult for an executive team to make key decisions about where to invest or forecast what revenue will look like.

At App Annie, where I went to work after Yammer, I became more convinced than ever of sales operations’ importance. At the time, the mobile app store analytics company had just reached product-market fit. We were successfully selling our product to mobile gaming studios that wanted to understand who was searching for their games and how they were reaching the app. But that market was limited. We had raised venture money and knew that we had to expand to new horizons if we were going to join the unicorn club.

Shortly before joining App Annie, I had re-read Crossing the Chasm, a book all about expanding to new markets. In the book, author Geoffrey Moore breaks buyers down into four groups: early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards. The gaming studios were our early adopters. They had high appetites for risk and wanted to use the latest technology. The challenge was identifying what our early majority market would be.

One of the things that I noticed looking at our early customer data was the prevalence of “sexy” brands. We didn’t have many large customers, but the ones we did were some of the most well-known brands in the world. In a meeting with Oliver Lo, who was our VP of Marketing, we decided that the reason was intuitive: companies that care about their brand were investing in mobile apps. The next quarter, we decided to create marketing and sales campaigns targeting these companies. Once again, I hired an army of interns to build a list of Directors of Brand and VPs of Digital Marketing at Fortune 500 companies. Then our SDRs started contacting them.

From the response and close data, we were able to validate the hypothesis further. We noticed that companies like Nestlé and McDonald’s not only responded but cruised through our sales cycle quickly.

Of course, today there are products that automate all of this. Products like Infer and EverString help sales teams identify the common attributes among their customers and then find more prospects like them. But as complicated as the technology behind those apps is, the underlying premise is simple business strategy: figure out what is working and then try to replicate it. At every sales organization I’ve ever worked at that task falls on sales operations.

Lesson 2: Use data to inform business strategy

One of the things that I had always heard from my colleagues at App Annie and Yammer was that a sales rep should always avoid being single-threaded. That is, during the sales cycle, a rep should include multiple contacts at a company in the conversation. If they first speak with a VP of Sales, they should ask, “Who else should we include in this conversation?” The reason is pretty simple: prospects often go dark on you. A VP of Sales might leave the company or go on a six-month sabbatical, and you don’t want all your eggs—or that six-figure commission check—in one basket. At Yammer, we required a discussion with the company’s IT team in order to pass their security requirements.

But I’ve been in sales long enough to know that there are a lot of myths and anecdotes that get passed along without any data to support their accuracy. So when I arrived at Datahug in 2014, I asked someone on the product team to check into the “Single-Threaded Theory.” One of the benefits of joining the company was that we were selling to sales teams, so for the first time in my career I was the end user of the product I was pushing.

Shortly after I put in the request, Ray Smith, Datahug’s CEO, had the engineering team anonymize our user data, crunch it, and build a report. In his findings, we learned that if you paired the engagement data—the frequency of emails between a rep and prospect—with the salesperson’s forecast, you could almost perfectly predict whether or not a deal would close based on that engagement. We also learned that there was a strong correlation between engagement and the number of contacts in an opportunity being communicated with. More engaged contacts meant more conversations throughout the sales cycle, which meant higher close rates. In other words, the Single-Threaded Theory was proven true.

At around that same time, LinkedIn launched a new feature where on each user’s profile they recommended similar profiles. This “People Also Viewed” feature was a goldmine for sales reps, especially with the Single-Threaded Theory in mind. The data team at LinkedIn was doing my job for me by analyzing similarities in profiles and handing them over. They organized people that worked on the same teams, communicated frequently, and reported to one another. So on a VP of Sales’ profile, we could see the reps that reported to them and the Director of Sales at that company, as they were almost always the most frequent profiles that were also viewed. That summer, I hired my third army of interns to go through each of our opportunities in Salesforce and go to their LinkedIn profile to add the names and titles from each People Also Viewed profile.

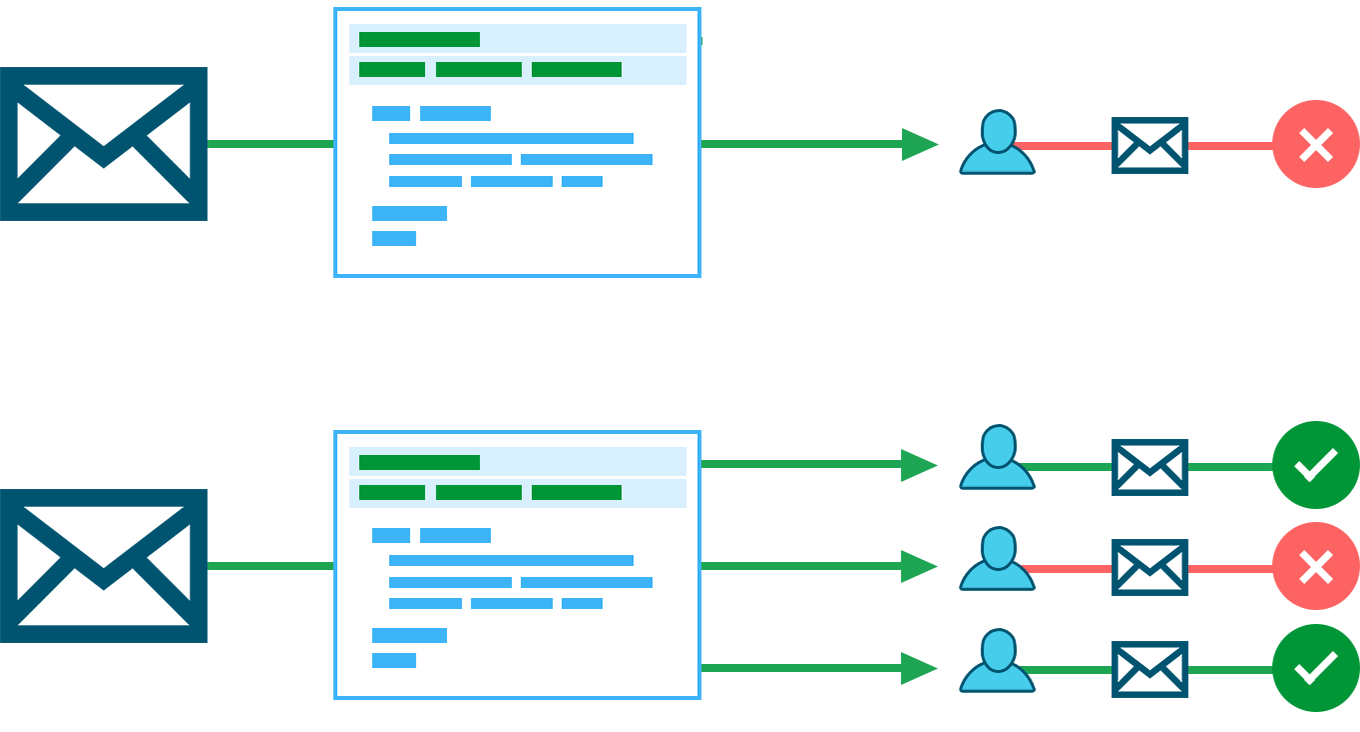

But once we had more than one contact per account, we started running into another problem. Salespeople always look for the path of least resistance and our team was no exception. They were given accounts with 10 contacts in some cases, and rather than tailor emails to each individual, they pasted in the same email copy and fired away. The results were less than ideal. To solve this, we worked with our marketing team to write copy and create cadences for each customer persona. Sure enough, the response rate went up and face-palm moments went down.

Lesson 3: Don’t let your reps get single-threaded

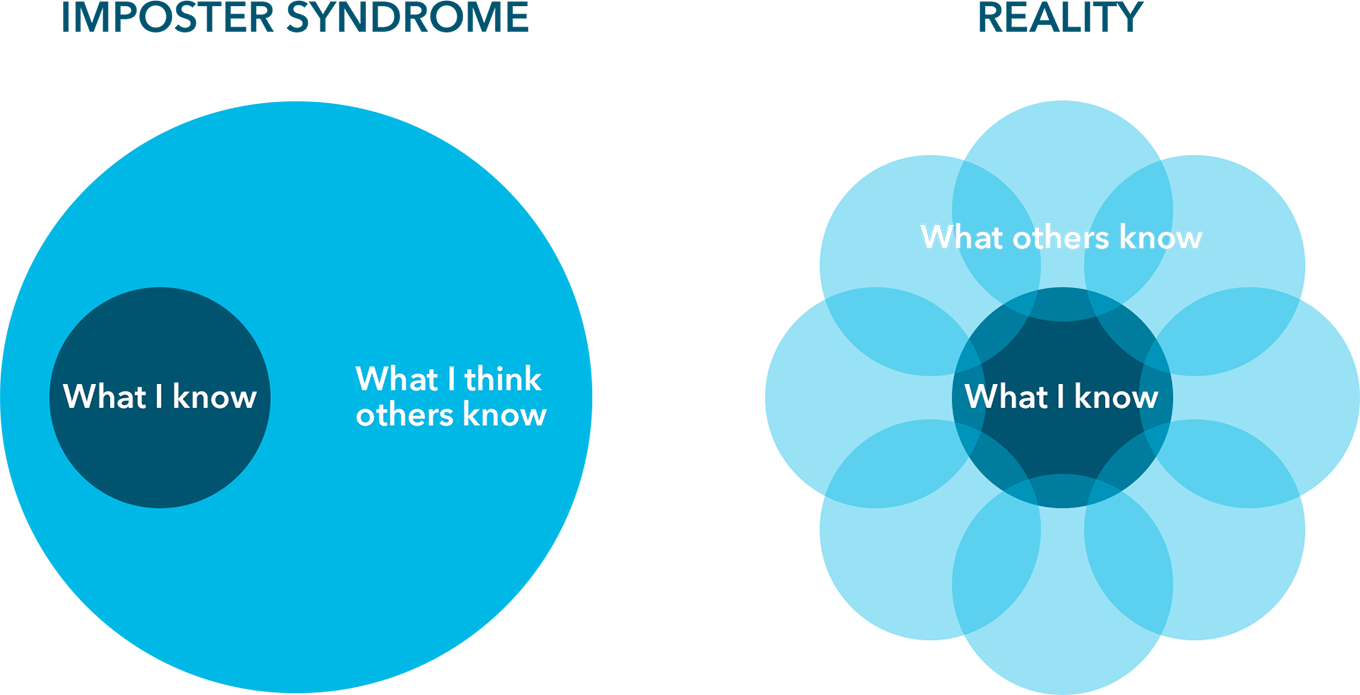

When I first started working in sales operations, I vividly remember coming home each day thinking two things: first, I thought I was in the wrong role because of the amount of mistakes I made, and second, I thought the problem immediately in front of me had no solution. My imposter syndrome—something that nearly every professional feels early in their career—has since gone away, and now whenever I run up against a hard problem, I have faith that my team and I will be able to solve it. But those evolutions in mindset didn’t happen naturally or easily.

I’ve been lucky to spend most of my career in a place with a high density of sales operations leaders. It seems that each week there is an event in San Francisco that I can attend and learn something new. It was at Meetups and happy hours that I began to see that everyone in sales operations feels more or less the same way. We’re all stumbling our way through problems and inevitably feeling stressed when we can’t solve them. Paradoxically, the smartest people I’ve met in the industry are the ones who are the first to admit what they don’t know. They ask questions at these events, listen more than they talk, and are honest about the challenges facing their business.

So I guess that’s my last piece of advice for the sales operations folks reading this. No one really knows what they’re doing, but we’re all in this together. So don’t stress, don’t be afraid to ask for help, and attend a happy hour (or two) to meet folks dealing with the same challenges you face.